This post responds to the Reply All podcast from the 7th of July 2016 entitled Disappeared. If you would like to listen to it first, the link is: https://gimletmedia.com/episode/69-disappeared/. I will be focusing on the second half of the podcast from 19 minutes onward. However, the first half is an equally fascinating discussion about Left-Pad, Azer Koçulu, and opensource licensing of code, which I equally recommend that you listen to.

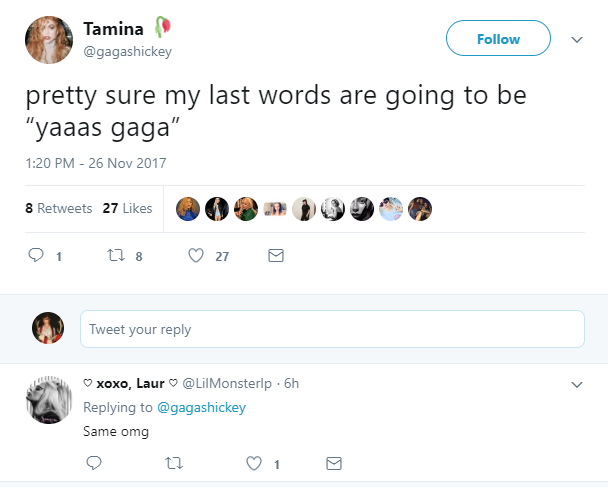

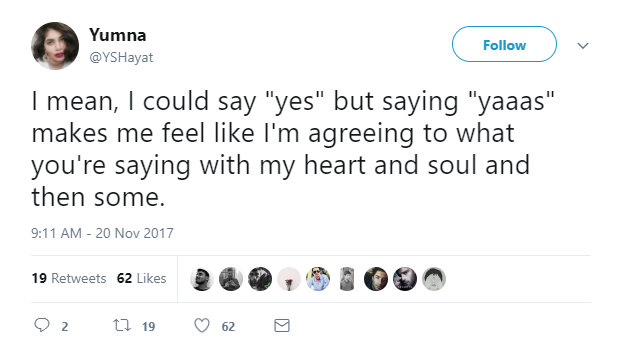

That being said, the second half explores the origins of the term ‘yas’, which is an incredibly popular way of expressing an intense appreciation for something or someone on the internet; any brief jaunt through Twitter, Tumblr, or potentially Facebook will undoubtedly return at least one use of it. For example (credit for all tweets given to the original account holders):

The tweet above appears to relate to the viral video that is credited with bringing ‘yas’ into popular culture, as is referenced in the Reply All podcast.

This tweet (above) is also interesting from an analysis perspective, and potentially offers an explanation for the popularity of the expression. It also engages with an interesting facet of drag culture as an exaggeration of stereotypes or gendered characteristics, as well as performed expressions of emotion.

There are even gifs of velociraptors from Jurassic World with ‘yas’ superimposed upon them:

Returning to the original usage, however, I myself have used ‘yas’ on Twitter multiple times in response to things I loved. However, quite shamefully, I had no idea of its etymology. The Reply All podcast informed me that it first appeared in Harlem in the 1980s as a part of ball culture – specifically drag balls. Here is the origin of my shame as one of the communities with which I identify most as a bisexual woman is the LGBTQIA+ community. Clearly, I need to widen my knowledge of LGBTQIA+ history beyond UK borders. Regardless, learning about ball culture, the related house families that took in young, queer Black and Latinx people, and hearing Jose Xtravaganza speak about his own experiences with the House of Xtravaganza (of which he is now the Father) was both enlightening and emotive. I later went on to watch Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris is Burning, which offers an intimate portrayal of multiple drag balls and speaks to numerous queens about their backgrounds and their experiences of being drag queens in New York City. It is an amazing and incredibly emotional documentary. It also expanded upon the Reply All podcast for me, in that the queens in Paris is Burning explain the meaning behind many more popular terms used at drag balls, almost all of which I have seen and heard used online today. I recommend that you watch the documentary for a better understanding than I can provide in a short blog post.

The main thing that irritates me about the popular culture usage of ‘yas’ and other drag terms is not the fact that they have been popularised, per se, but that they have been popularised at the expense of their cultural heritage. I have no problem with multitudes of people using these words, but they have no idea of the atmosphere in which they were birthed. The vast majority of people using these words don’t understand why the subculture from which they come came into being; they don’t appreciate the immense hardships that these groups of people faced, or the relief of the sense of belonging that using these words and understanding them within gay culture gave. They are now part of mass culture. It feels almost as if by absorbing and appropriating gay language, popular culture has subsumed gay subculture, taken what it wanted, and spat the gay people out as ‘still not accepted’. It doesn’t come from a place of welcoming acceptance of gay culture and inclusion of popular slang used by the gay community with knowledge of the words’ heritage; it just lifts the word and erases its past and present as a ‘gay’ word. Homophobic people, transphobic people, biphobic people – people who are just unnaccepting of any and all parts of queer life and the queer subculture use ‘yas’ both online and in real life.

It is ironic in a way that a word with a queer history exists in the mouths of people who would absolutely ‘gag’ – in the basic sense of the word – and wash away all traces of it if they knew it had been used to celebrate drag queens and positive queer youth culture. But it also just stings. Part of the balls in Harlem was a competition to see if people could ‘pass’ for a certain gender or social class: they played with normative culture, and now one of their celebratory words is normative culture, but without them. It is still used by queer subcultures online, but many of those people are equally as unaware of the origins of one of their most-used words as I was. I think the main thing that saddens me is just that the revival of a word into mass usage doesn’t necessarily mean that social or societal groups are progressing and diversifying, but almost that popular culture is continually homogenising history and subculture into a mulch of ‘accepted’ popular culture. Words are stolen, repurposed, or even used in the way in which they were originally intended, but by different groups of people that cast them as monochromatic.

Popularising gay culture and drag culture is in no way bad when it reflects a more positive attitude towards LGBTQIA+ people: this is incredibly necessary, and a wider occurence of positive attitudes towards queerness would save so many people so much pain. But I don’t feel like that’s what this is. For me, and in my experience, the success of ‘popular gay culture’ like Ru Paul’s Drag Race has been mostly down to a fetishization and exoticising of gay culture for a straight, cisgendered audience who want to ogle the exiled ‘different’ people and the way in which ‘they’ live. There are, of course, LGBTQIA+ people who adore Ru Paul and feel represented by it, but its encouragement of stereotypes and high-performance ‘gayness’ has often been a turn-off for me and others in my own life. I do not speak for everyone and I am not trying to, but this is my personal discomfort with the ways in which ‘popular gay culture’ is sold.

I think that by educating anyone and everyone who uses the word ‘yas’, or any of the other terminology that originates in drag culture, we could solve the problem of it being appropriative. That way, those who are accepting of its origins and willing to continue the process of educating others can continue to use the words, fully aware of their history, and anyone who is upset by gay or drag culture will probably dislike the taste of ‘yas’, and cease to use it, thus eliminating the appropriation.

Some links for further reading/ watching:

- Paris is Burning can be found on Netflix.

- Reply All podcast number 69: Disappeared. https://gimletmedia.com/episode/69-disappeared/

- https://www.pride.com/movies/2015/5/20/10-things-paris-burning-taught-us

- Drag terminology explained: https://www.reddit.com/r/rupaulsdragrace/comments/1zpy2z/drag_terminology_explained_for_the_newbies_like_me/

- An interesting article by Edward Canlon about Dorian Corey, one of the stars of Paris is Burning. TW for disturbing events. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2935316?seq=12#page_scan_tab_contents